From the pages of our program, read Andy McLean's essay on Twelfth Night as he experienced the production from the rehearsal room to stage.

Twelfth Night or What You Will is a comedy disguised as a tragedy. A play where nobody is quite who they think they are. Where no place is what it appears to be. And where love is – simultaneously – the best thing in the world and the absolute worst.

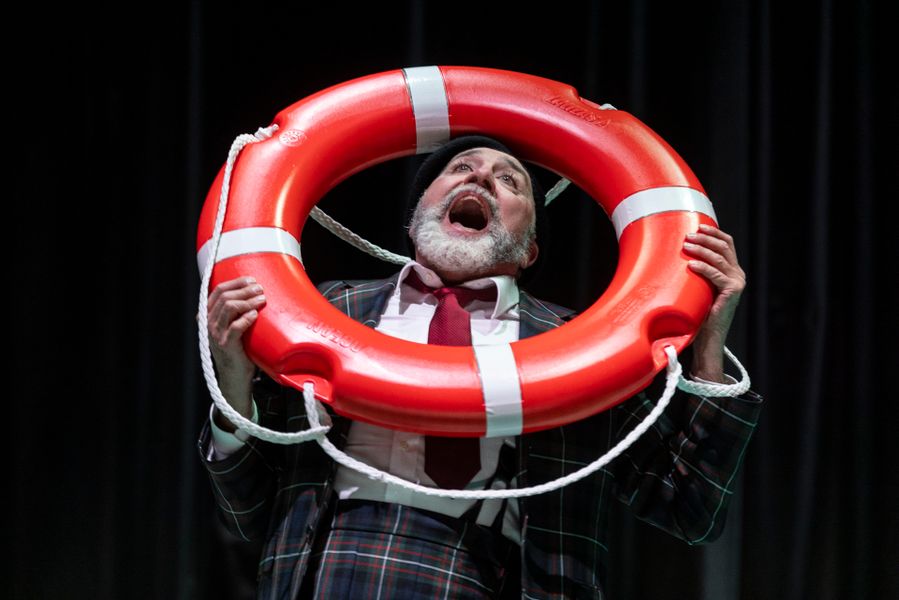

Rest assured, this production makes good on Twelfth Night’s comedic promise. It’s funny – often painfully so. Whether it’s Maria’s ruse to humiliate Malvolia, or Sir Toby poking fun at Sir Andrew, the jokes land hard (often coming at someone else’s expense). Meanwhile, Sarah Blasko’s melancholy music gently lingers over our laughter like a question mark.

I AM NOT WHAT I AM

Much of the humour stems from Shakespeare’s penchant for bamboozling his characters. Orsino believes he’s profoundly in love with Olivia (whom he barely knows) when it’s obvious he’s actually falling for a guy named Cesario (who is, in fact, a girl named Viola in disguise). Olivia also falls for Viola (believing her to be Cesario) before mistakenly marrying Viola’s twin, Sebastian. And in his hour of greatest need, Antonio wrongly believes he’s been betrayed by his beloved Sebastian (again, it’s actually Viola in disguise).

Time and again, characters in this play are deceived by themselves as much as by one another.

In fact, so shifty was Shakespeare that he may have outwitted himself. He set Twelfth Night in ancient Illyria (on the Balkan Peninsula, famous for pirates and shipwrecks) but his characters occasionally slip London references into conversation. Antonio, for example, recommends Sebastian stays “in the south suburbs, at the Elephant”, just down the road from where Shakespeare’s company performed. (We can only speculate as to why the writer did this. Maybe it was carelessness; or maybe it was the Elizabethan equivalent of product placement in movies.)

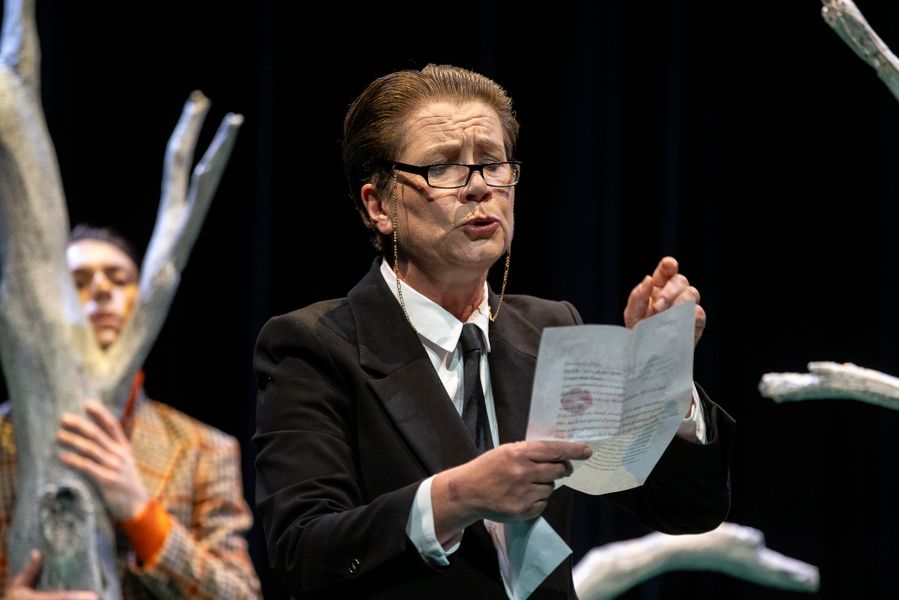

Whatever Shakespeare’s reasons, by playing fast and loose with locales, he left an open invitation for future theatre makers to also do “what you will” with their staging. For this Bell Shakespeare production, designer Charles Davis has created an ahistorical setting – existing outside of time or place – to let the storytelling shine.

GROANS THAT THUNDER LOVE

Perhaps the trickiest move by Shakespeare in Twelfth Night though is to take the purest, most joyful thing in the world – love – and turn it into a source of discord and sorrow. While no two characters talk the same way about love, most of them are tormented by it in one way or another.

Right from the opening scene, Duke Orsino makes romance sound like a desperate bloodsport: “And my desires, like fell and cruel hounds, / E’er since pursue me.” He then spends most of the play agonising over the resolutely unattainable Olivia.

Viola’s affection for Orsino becomes an exquisite form of torture when he despatches her to woo Olivia on his behalf. In doing so, Viola eloquently articulates her own heartache: “With groans that thunder love, with sighs of fire.”

Nothing good comes from Viola’s heart-rending words. Instead, Olivia immediately starts yearning for Viola. Olivia’s description of this (“Even so quickly may one catch the plague”) is one of numerous occasions when characters associate love with illness. Sir Toby describes Feste’s tender love song as “A contagious breath” and Olivia accuses Malvolia of being “sick of self-love”. Orsino even suggests that love can be fatal (“But died thy sister of her love, my boy?”) and another Feste ballad laments, “I am slain by a fair cruel maid”.

Shakespeare doesn’t spare his minor characters from heartache either. Late in the play, Sebastian expresses the anguish of separation from his beloved Antonio (“Antonio! O my dear Antonio! / How the hours have rack’d and totur’d me / Since I have lost thee!”). For his part, Antonio’s devotion to Sebastian gets him arrested. And it seems even Sir Andrew has been scarred by love, when he despondently confides in Sir Toby, “I was adored once, too”.

ALL IS FORTUNE

Shakespeare also shows us the cynical side of love. Sir Toby falsely promises Olivia’s ardour to fleece Sir Andrew of his money and Malvolia, too, sees love as a means to an end. When she’s hoodwinked into believing Olivia fancies her, Malvolia immediately fantasises about the material trappings of becoming a countess, and how she’ll use her status to settle petty scores.

As for Olivia, she seems to think love can be purchased (“Youth is bought more oft than begged or borrowed”). Her first attempt to win Viola’s heart is to send her a ring. Next, she gives a locket. And later pearls (which she accidentally gifts to Sebastian).

Familial love is also a source of pain in Twelfth Night. We first meet Olivia languishing in the loss of her recently deceased brother and father. (As Sir Toby puts it: “What a plague means my niece to take the death of her brother thus? I am sure care’s an enemy to life.”) Meanwhile, twins Viola and Sebastian spend most of the play fearing the other has drowned.

In this production it's apt that Shakespeare’s shiftiest tricksters – Maria and Feste – don’t want a buttery bar of love. Here, Maria wisely sidesteps any romance with Sir Toby as well as Sir Andrew. (Let’s face it, Maria was always way too smart to settle for Sir Toby anyway.) And Feste flits between Orsino’s court and Olivia’s household, gleefully pointing out the lunacy of love. Professionally, Feste may be a Fool, but he’s seen the evidence all around him. He knows that love makes true fools of us all.

Andy McLean is a writer who grew up in Stratford-upon-Avon, before following the Bard to London. Unlike Shakespeare, he now lives in Sydney.